Oiled females that have recovered sufficiently to swim and groom normally prior to delivery appear to have the greatest success in raising a pup. Pregnant otters that are unoiled or are captured more than eight weeks following a spill are also more likely to successfully deliver and raise a pup. These otters should be handled as little as possible, housed in large seawater pools, fed, and observed regularly according to standard husbandry protocols (see Chapter 7). The holding pool may house other compatible females, but these animals may have to be removed after delivery if they interfere with the mother in feeding or caring for her pup, or if care of the other otters disturbs the new mother. Pup stealing has been observed frequently in captive sea otters and may create problems if the mother is inexperienced or too debilitated to protect the pup from such interference.

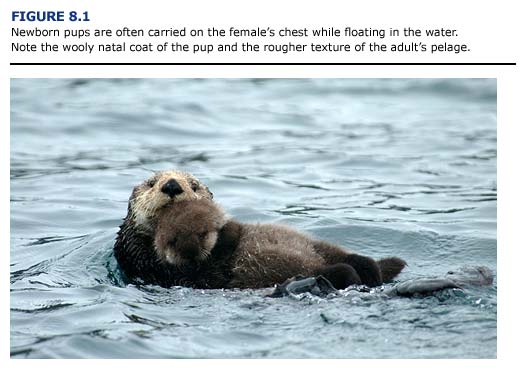

Most otters deliver after relatively short periods of obvious labor, regardless of whether they are in the water or on a dry surface. Some females with free access to water choose to complete their labor on haul out areas. The onset of labor is frequently signaled by a sudden loss of appetite and increased attention to grooming of the vaginal area. Some females appear to rub their lower abdomen which may assist contractions, and most will alternate periods of straining on the haul out with frequent periods of swimming, including vigorous rolling and grooming behaviors. After delivery, the female usually floats on her back in the water and holds the newborn pup on her chest while she licks and dries its fur (Figure 8.1). The placenta will usually be observed trailing from the vaginal opening for up to two hours after delivery. Eventual passage of these membranes appears to cause the female no distress. A moderate bloody discharge also may be observed during the first post partum day, but is seldom noted after that time.

Once the mother has completed grooming and drying her newborn, a healthy pup will usually move onto the female’s lower abdomen and nurse. The pup will remain nursing and sleeping on its mother’s upturned chest and abdomen for the next three to four weeks, except for short periods when she places the pup on a haulout or leaves it floating on the surface of the water while she feeds or grooms. A pup will vocalize loudly during these short separations and will gradually start to perform simple swimming movements, beginning with the ability to roll onto its back.

Haulouts should be designed to allow females to crawl out of the water without dragging the pup against a sharp edge. Pups can become trapped in overflow outlets or under haulouts unless such structures are adequately enclosed. Pools designed to hold young pups and their mothers should have haul out space which can be gated to separate the animals without undue stress while the pool is cleaned and disinfected. Alternatively, floating maternity pens can be constructed in the prerelease facility. (See Chapter 12 for a description of the different types of enclosures.)

Stillborn pups may be groomed and carried for several hours before the female loses interest. Females may become frantic when handlers attempt to remove weak or dead pups. As a result, a pup may be drowned or crushed if the female will not abandon it. Female otters which are unable to float on the water due to poor coat condition or medical problems can perform pup grooming while in a dry cage. However, they will probably be unable to successfully nurse their offspring.

Once a healthy pup has become bonded to its mother, short separations for purposes of medical treatment or movement within the rehabilitation center cause few problems. When mothers and pups must be separated during transport, it is preferable to place cages so that they may remain in visual contact. In at least one case, a three-month-old pup separated from its mother for medical reasons for more than seven weeks was able to reestablish the maternal bond within twenty-four hours after its return to the mother (J. McBain, Sea World; personal communication).

The high rate of neonatal death can be extremely distressing to the husbandry staff. This problem should be anticipated and addressed during training with special attention to protocols for handling otters whose pups die. Only one or two people should be allowed in the vicinity of any newborn and its mother. Movement of animals for treatment or pen cleaning should be postponed as long as possible, and then performed efficiently by well-trained handlers. In view of the poor survival rate of pups born to otters early in a rehabilitation program, it may be preferable to allow the female otter to care for its pup with minimal interference. A pup that dies in this circumstance can be removed after the mother abandons it without creating undue stress to the female or the staff.

If a decision is made to remove a pup and care for it in a nursery, it may be preferable to do so before the pup nurses; females exposed to crude oil may transfer petroleum hydrocarbons through the colostrum (see following section). In these cases, the benefits of nursing must be balanced against the potential exposure to petroleum hydrocarbons in the mother’s milk. When removing a pup, the mother should be distracted with food or otherwise separated from her pup while a second handler approaches and removes the pup with a net.

Lactating female sea otters have been observed to adopt young pups in a variety of situations (Reidman and Estes, 1990). The successful raising of a pup by a surrogate female in captivity has been reported. This deserves further investigation as an alternative to nursery care for orphaned or abandoned pups.

Lactating females will have a higher nutritional requirement than non-lactating otters (see Chapter 7 for normal dietary requirements). Food should be offered in larger amounts and at more frequent intervals throughout the day (up to 50% body weight per twenty-four hours).